Managing Tax Drag When Diversifying Your Portfolio

We recently talked to a longtime Facebook engineer who was trying to figure out the best way to diversify his META stocks. He usually just sold the stocks to buy a diversified ETF, but he wasn’t thinking about tax drag. It’s a concept that he (and you) need to understand to make fully-informed investment decisions.

When you own a stock that has gone way up in value, you may face a tough choice. If you hold your position, you’re exposed to the concentration risk of having a lot of your net worth tied up in a potentially volatile stock. Unfortunately, selling that stock to diversify your portfolio, can mean paying capital gains taxes of 35% or more.

Benjamin Franklin said “nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.” Some wealth managers would tell you it is beneficial to combine the two – and to defer taxes until the end of your life. However, many of us need money or prefer to diversify during our lifetimes. When you pay taxes to switch from one investment to another, you have less post-tax capital to invest in the market, and your capital compounds more slowly on an absolute basis. That’s tax drag at work.

What is tax drag?

Tax drag describes the ongoing negative impact paying taxes can have on an investor’s overall returns. It can occur when switching from one investment to another and triggering a taxable event (like the Facebook engineer we mentioned).

When you pay taxes, the amount of principal you have to invest decreases. It’s a little like throwing away years of growth in your portfolio. As your investment compounds over time, the returns are lower because there’s less principal to compound.

In certain circumstances, tax drag can be limited if you can either avoid paying the taxes altogether, defer the taxes and pay them later, or find ways to offset the capital gains with capital losses. We’ll explain all these scenarios below.

{{black-diversify}}

An example of tax drag

To see tax drag in action, let’s return to the early Facebook engineer we mentioned at the beginning of this piece.

The engineer is a high earner in California, which means he could have an effective capital gains rate of 35%. His cost basis for the META stock he earned as compensation is negligible, which means every $100K in META that he wants to sell and diversify would incur $35K in taxes.

If he re-invested the remaining $65K in a diversified fund, it would take almost five years to return to his starting point of $100K, assuming an average annual return of 10%.

On the other hand, a dollar of tax that’s deferred is a dollar that's out working for you. Over time, this can compound to a huge advantage even if you pay all the taxes down the line.

If the Facebook engineer was able to diversify his holdings without a sale, his $100K investment would be worth 54% more than in the scenario where he paid taxes to diversify – assuming the same 10% growth rate over five years.

As you can see from the example above, the impact of compounding returns would continue over time for the Facebook engineer. If he waited 10 years to sell and pay taxes on his tax-deferred portfolio, his post-tax returns would be almost 27% higher than if he paid tax up front. You can see the effect of compounding interest clearly when you plot the 10% returns over time on a chart:

Calculating tax drag

Modeling out the potential tax drag on your portfolio can take a little spreadsheet wizardry, so we created a tax drag calculator that makes it a little easier to understand your situation. If you know your cost basis and the approximate value of the stock you own, check out our simulator.

It calculates and compares the different outcomes if you decide to diversify and sell or participate in a tax-deferred exchange fund. The outcome with an exchange fund should be similar to the example we showed you above, however using numbers that approximate your situation can help drive home how much tax drag could potentially hurt your long term performance.

How to optimize tax drag

Tax drag does not have to be a fact of life!

Let’s be clear: Taxes are (nearly) always incurred when you sell your assets (e.g. to raise cash to buy a house or other financial needs). However, when you are selling one investment to buy another, tax drag can be optimized and should be a serious consideration.

The tax code provides quite a few ways to optimize your portfolio. Like-kind exchanges (like exchange funds), tax-loss harvesting, gifts and charitable trusts can all provide ways to keep taxes from eating into your principal. Here are a few quick details on each approach:

However you choose to proceed, it can definitely be worth your while to explore your options. Your head is in the right place if you’re thinking about diversifying and selling. Take the extra time to calculate the potential tax drag on your portfolio, and if you’re unsure of your options, talk to an advisor about the best ways to meet your investment objectives.

More about exchange funds

After being in the exact same situation as the Facebook engineer we’ve discussed, we did the same research you’re doing today.

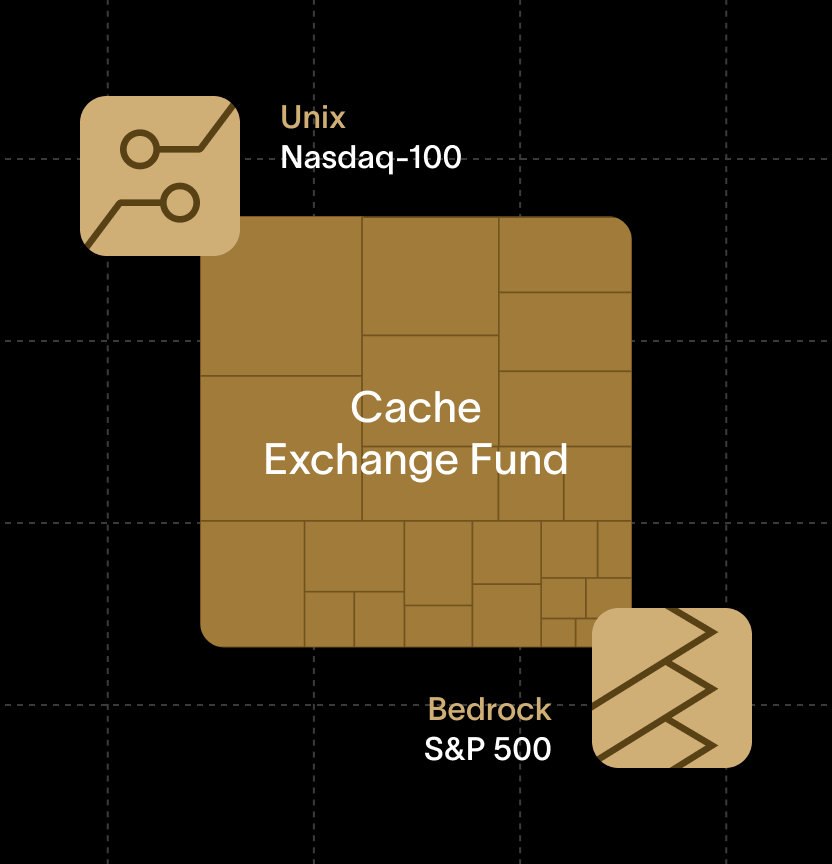

We believe that like-kind exchanges, enabled by exchange funds, are a powerful solution for avoiding tax drag. In fact, we believe it so strongly that we founded this company, Cache, to bring them to individual accredited investors for the first time.

To be eligible for a modern exchange fund (like the one Cache offers), you must meet the SEC’s definition of an accredited investor. You also must invest a minimum contribution of $100,000, have the financial stability to commit for at least seven years, and be aware of the following risks associated with exchange funds: limited liquidity, investment constraints, and the potential for tax law changes. Diversification reduces concentration risk, but it does not eliminate investment risk completely. It is still possible to lose principal when you participate in an exchange fund.

You can take a deep dive on exchange funds if you really want to understand them, or see how direct indexing compares to exchange funds. We’d also be happy to answer any of your questions if you want to tell us a little more about your situation!

<div class="blog_disclosures-text">Material presented in this article is gathered from sources that we believe to be reliable. We do not guarantee the accuracy of the information it contains. This article may not be a complete discussion of all material facts and is not intended as the primary basis for your investment decisions. All content is for general informational purposes only and does not take into account your individual circumstances, financial situation, or your specific needs, nor does it present a personalized recommendation to you. It is not intended to provide legal, accounting, tax or investment advice. Investing involves risk, including the loss of principal.</div>

{{black-diversify}}